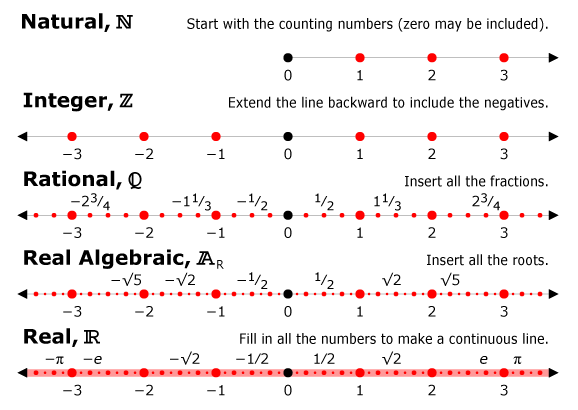

In proof based math, we study objects in a very unique way. We might have an example of some object, for instance, the natural numbers. We may know how the natural numbers behave (some properties like associativity), but how do we know what the natural numbers actually are? Well, for mathematicians, what something “is” is the same as how that thing “acts.” For example, we could say that an object “x” is a natural number if it’s an element of the set {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, …}. This definition is somewhat informal (we haven’t defined what a set is yet), but ignoring that, does this definition imply that Roman numerals (along with zero) aren’t natural numbers? Not necessarily – the Roman numerals (with zero) act exactly the same as the Arabic numerals. So, maybe there are multiple versions of “the set of natural numbers.” But all of these versions will act in exactly the same way. For example, IV + V = IX is just another way of saying 4 + 5 = 9. Any statement you can make about Arabic numerals, you can also make about our modified Roman numerals. If two objects act exactly the same, like the Arabic and Roman numerals, we say they are the same up to “isomorphism.”

To summarize, when we say two things are the same up to “isomorphism,” we mean “these objects may look different, but they act exactly the same.” And for our purposes, if two sets act the same way, they are considered the same, even if they “look” different.

For a more extreme example, consider the set {0, 2, 4, 6, 8, …}. Would it be wrong to call this the set of natural numbers? If your answer is yes, then why? After all, this set behaves exactly like {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, …}. The only difference is that I’ve replaced “1” with “2,” “3” with “6,” etc. That’s basically the core of what it means for two objects to be isomorphic: an isomorphism is a kind of relabeling.

So how do we know if something is a set of natural numbers? There must be a few properties such that if a set satisfies these properties, then it can be considered a set of natural numbers.

Well, first of all, these properties have to describe the way natural numbers interact with each other. Mathematicians care more about how things act than what they are. But how can we discuss how the natural numbers act if we don’t know what they are? We can’t define exponentiation if we haven’t defined multiplication, and we can’t define multiplication if we haven’t defined addition (or at least it would be really hard). So maybe we should start with the following property, or “axiom.”

Axiom I: There is a set (for now, a set is just a collection of things called elements) called the natural numbers, along with an object called “+.” We denote this set as “ .”

.”

But wait, isn’t there something simpler than addition? That’s right — counting! Addition is basically just repeated counting. Let’s say that if “n” is a natural number, then n++ is “the next natural number.” Now we can refine our first axiom:

Axiom I (revised): There is a set called  along with an object called “++.”

along with an object called “++.”

Keep in mind, “object” here just means “thing.” Operations are objects, but since we haven’t formally defined what an operation is yet, we’ll just say “object.”

This doesn’t tell us much about what natural numbers are, though. Let’s think: what do we know about natural numbers? Well, we know 0 is a natural number.

Axiom II: There exists an object called $0$ that is an element of  .

.

In math language, “is an element of” is written as “”. To say “there exists,” you’d write “

.”

Axiom II (restated):

That’s the “math” way of saying “There exists a thing called 0 in the set of natural numbers.” For now, a set is just a collection of elements.

We also know that if is a natural number, then

is also a natural number. In math language, “implies” is written as

. So now we have:

Axiom III:

This translates to “n is a natural number implies n++ is a natural number.”

But we don’t actually know anything about . We could just say the natural numbers are the elements of the set

, with

and

. That satisfies our properties so far, but it doesn’t give us the infinite set of numbers we want. We want the natural numbers to go on forever, so to prevent them from “looping around,” we say that 0 can’t be the successor of any natural number. In math, “there doesn’t exist” is written as

. So to say there isn’t a number whose successor is 0, we write:

Axiom IV:

The vertical bar means “such that.” Sometimes you’ll see a colon or comma instead of the bar.

Okay, but what if I say the natural numbers are just the set {0, 1} with , and

? That system also satisfies our axioms so far. But we don’t want the problem of “hitting a wall” where two different numbers share the same successor. So we ban two different natural numbers from having the same successor. In other words, if

, then

:

Axiom V:

This seems to handle that. But what if our set actually has two copies of the natural numbers? For example: {O, 0, I, 1, II, 2, III, 3, …} with and

, etc. How do we rule this out? We look for a property that our standard natural numbers have but this “pathological” set doesn’t. We then add that property as another axiom. Think about it! Seriously. Pause and think.

Did you think about it?

Okay, the one I came up with is this: if I know something is true about , and I also know that if it’s true for one number, then it’s true for that number’s successor (

), then I can conclude it’s true for every number. This property—called the inductive property—holds for {0, 1, 2, 3, …}, but not for {O, 0, I, 1, II, 2, …}. To see why, consider the statement “k is an Arabic numeral.” It’s true about 0, and if it’s true for n, then it’s also true for n++ in our system. Yet we still have these weird duplicates. So we need to formalize a statement that closes that loophole.

In math language, to write “a statement that can depend on ,” we might write

or

, etc. So if I want to say “if

is true, then

is true,” I might write

. If I want to say “for all

, if

is true, then

is true,” I’d use

(meaning “for all”):

Axiom VI:

Note that we’re not saying is true for any specific k. We’re just saying that if it is true for k, then it will be true for k++. That, combined with knowing it’s true for 0, forces it to be true for all natural numbers. This is what we call the Induction Axiom.

Leave a comment