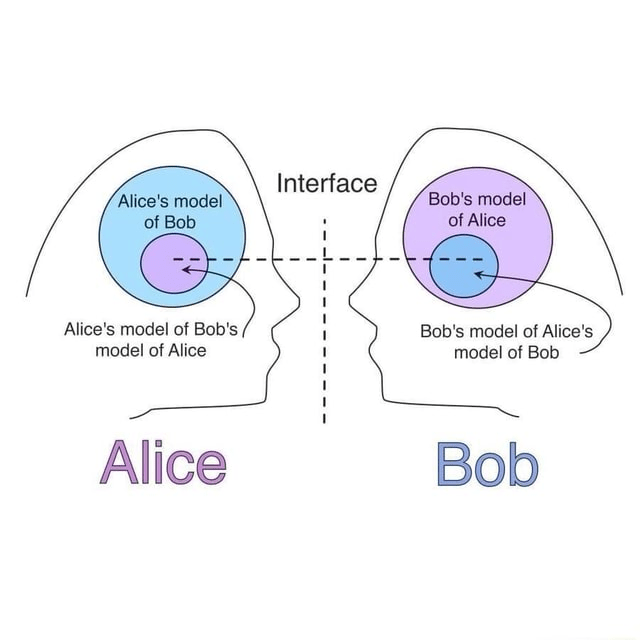

When you talk to someone, the person who is really speaking isn’t exactly “you” as you know yourself. It’s the version of you that exists in their mind: their internal model of who you are. They respond to that version, you respond to how they treat you, and the two of you shape each other in real time. When someone treats you like you’re capable, sharp, or insightful, you often find yourself acting that way. When they treat you like you’re slow, unimportant, or secondary, that has a way of pulling you downward too. The people around you don’t just react to you; they help build you, and you do the same to them. Over time, you start to pick up their language, their tone, the way they think, and they quietly pick up parts of you as well. You can see it in small things, like friends borrowing your phrases, and in larger things, like the kind of person you gradually become by staying close to certain minds.

If that’s how social life works, you might wonder why we don’t simply transform into whatever the people around us believe we can be. Why doesn’t someone who’s treated like a genius always rise to that level? Well, you don’t only want to be admired or seen positively; you also want to feel consistent with your own story about who you are. If your internal narrative says “I’m incompetent,” being treated like a savant doesn’t feel encouraging, it feels threatening, like reality has gone out of alignment. So you may unconsciously pull yourself back down to match the story you already believe. You protect the familiar version of yourself, even when it limits you.

But not everyone resists change in the same way. People high in openness to experience are more willing to let new perspectives reshape them. They tend to be curious, comfortable with uncertainty, and willing to let experiences shift their sense of self. Their identity has some give to it, so when someone treats them as more capable, more thoughtful, or more complex, they are more likely to absorb that treatment and let it update who they are.

So, many people who score on the low end of openness to experience end up with this strange tension built into social life. On the one hand, other people are constantly offering us versions of ourselves to grow into. On the other hand, they often cling to the older, smaller versions because they feel familiar. And when someone is open enough, psychologically and temperamentally, to let those new models seep in, something remarkable can happen. Their identity doesn’t feel like a fragile object that must be defended, but like an ongoing process that can be revised. And that openness does not just exist at the level of beliefs or personality; it shows up physically, in the brain itself.

There is this fascinating line of research showing when you are really listening to someone tell a story, your brain does not behave like a passive recorder. Instead, your brain begins to align with theirs. Neural activity in the speaker’s brain and neural activity in your brain start to follow the same rhythm across regions involved in language, meaning, and narrative. While they are building the story internally, you are rebuilding it inside your own nervous system, almost in synchrony. It is not poetry to say you are “on the same wavelength”; in a real sense, you are.

Of course, biology still imposes delays. You usually lag behind them a little because your brain needs time to process what they have said. But in some regions, something even more interesting happens: you get ahead of them. Your brain starts predicting what comes next. It is already preparing the next step in the thought, anticipating the next turn in the idea. When communication is working, your predictions line up with theirs, and the conversation feels smooth, natural, almost effortless. When communication breaks down, it is not usually because the sounds didn’t reach your ears. It is because this shared neural pattern never formed. The coupling disappears. Two minds drift out of sync.

And the really striking thing is that the strength of this coupling actually tracks understanding. The closer your neural activity locks onto the speaker’s, the more deeply you comprehend. Understanding, then, is not something purely private; it is something that emerges between people when their brains manage to briefly coordinate.

If we put all of this together, a picture starts to form. Communication is not simply informational transfer. It is a joint construction of identity, meaning, and even neural state. When people understand you, they partially simulate you. And you do not simply react to others; you allow them to enter the structure of your mind, sometimes literally reshaping it. The extent to which that reshaping happens depends on openness, self-story, and the willingness to risk being influenced.

So when you talk to someone you care about, or someone who challenges you, or someone you admire, it is worth realizing what is actually happening. Two selves begin to lean toward one another. Two stories about “who I am” start negotiating. Two brains, for a brief moment, learn to think together. And depending on how rigid or flexible you are, that moment can either reinforce the person you already believe yourself to be, or it can quietly begin to write a better version.

Leave a comment