Mathematics is often considered the language that describes our physical universe. Equations precisely define the motions of planets, the flows of rivers, and the shapes of DNA molecules. Numbers quantify the sizes of galaxies, the charges of electrons, and the values of bank accounts. Math gives science its incredible predictive and explanatory power. But is math itself real? Or is it just a fictional game with made-up rules?

To answer this, we need to understand what mathematics is built on: axioms and theorems. Axioms are the basic assumed truths that provide the foundation. In Euclidean geometry, an example of an axiom is that parallel lines never intersect. Theorems are logical conclusions deduced from axioms. The Pythagorean Theorem, which states that the square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides, is a famous example. You need axioms, because nothing can be proven unless we have certain common things we assume to be true. In this sense, axioms do not necessarily model the real world. They are human creations, not fundamental truths. These axioms often model certain truths of our universe, but it truly is just an abstraction.

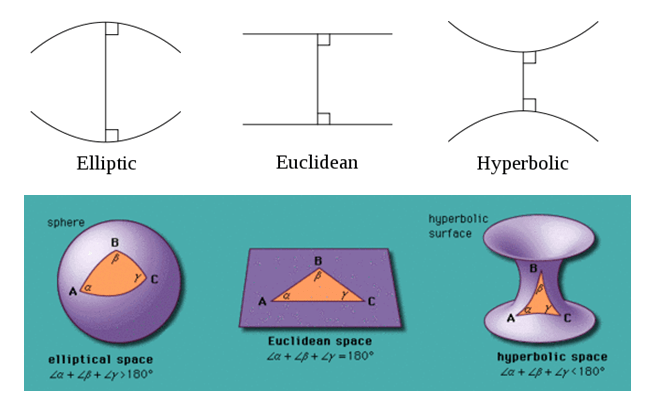

Different selection of axioms lead to different mathematical systems, like how non-Euclidean geometries can just reject or modify the parallel line axiom (more on that in a second). This suggests mathematics is more invented than discovered.

However, even if axioms are arbitrary human constructs, logically valid theorems are objectively true within the framework defined by the axioms. Given a set of axioms, some theorems inevitably follow, while others provably don’t. In this sense, theorems feel discovered, not created.

So which is math – invented or discovered? The answer is: both. Axioms are invented to create an abstract mathematical universe. Theorems are discovered as logical absolutes within that universe. Changing the axioms changes the theorems, giving different mathematical systems.

This means math itself is not an external truth about reality. Contrary to Plato’s philosophy, mathematical concepts don’t exist independent of humans. Math is not found, but constructed by us.

However, that doesn’t make math meaningless. Quite the opposite – we invent axioms that are useful for modeling aspects of reality. Geometry’s axioms elegantly capture our physical intuition about space, distance, and shapes. The axioms of calculus help describe change and motion. Number theory axioms model the concept of quantity.

Useful math articulates patterns that resonate with nature because we specifically designed it to. We crafted axioms to construct a mathematical universe aligned with our observations about the physical universe. Math models reality because we intentionally built it to reflect properties of the world we inhabit. This is why math is unreasonably effective in the natural sciences

But math can also be constructed to describe worlds that don’t exist. Mathematical systems built on alternative axioms deviate from physical reality yet remain logically valid. For example, hyperbolic geometry rejects the parallel line axiom, leading to radically different and non-intuitive theorems that don’t match our tangible experience (…kind of; hyperbolic geometry can help model certain curved figures like saddles). But hyperbolic geometry is fully self-consistent on its own terms.

This is why math is so powerful. Its axiomatic freedom lets it model reality precisely in some systems, diverge completely in others, and stretch possibility beyond imagination in others still. I think it is because math grants the ability to discover necessary logical relationships in artificially constructed worlds, while also encoding fundamental aspects of our natural universe.

Leave a reply to The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Math in the Natural Sciences – Micah Zarin Blog Cancel reply